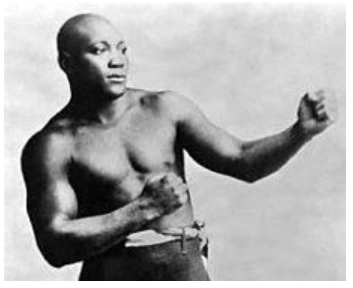

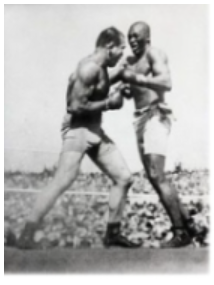

In 1910, former undefeated heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries came out of retirement and said, “I feel obligated to the sporting public at least to make an effort to reclaim the heavyweight championship for the white race. . . . I should step into the ring again and demonstrate that a white man is king of them all.” Jeffries had not fought in six years and had to lose weight to get back to his championship fighting weight.

The fight took place on July 4, 1910 in front of 20,000 people, at a ring built just for the occasion in downtown Reno, Nevada. Johnson proved stronger and more nimble than Jeffries. In the 15th round, after Jeffries had been knocked down twice for the first time in his career, his people called it quits to prevent Johnson from knocking him out.

The “Fight of the Century” earned Johnson $65,000 and silenced the critics, who had belittled Johnson’s previous victory over Tommy Burns as “empty,” claiming that Burns was a false champion since Jeffries had retired undefeated.

Riots and aftermath

The outcome of the fight triggered race riots that evening — the Fourth of July — all across the United States, from Texas and Colorado to New York and Washington, DC Johnson’s victory over Jeffries had dashed white dreams of finding a “great white hope” to defeat him. Many whites felt humiliated by the defeat of Jeffries.

Blacks, on the other hand, were jubilant, and celebrated Johnson’s great victory as a victory for racial advancement. Black poet William Waring Cuney later highlighted the black reaction to the fight in his poem “My Lord, What a Morning”. Around the country, blacks held spontaneous parades and gathered in prayer meetings.

Some “riots” were simply blacks celebrating in the streets. In certain cities, like Chicago, the police did not disturb the celebrations. But in other cities, the police and angry white citizens tried to subdue the revelers. Police interrupted several attempted lynchings. In all, “riots” occurred in more than 25 states and 50 cities. About 23 blacks and two whites died in the riots, and hundreds more were injured.